First human head-to-body transplant: Russian man to undergo revolutionary surgery

When I heard this story was shocked because I didn’t think it was possible. But, if you can believe it, there are now plans to do it. Do what? Transplant a human head onto another person’s body. Every person has challenges. For some, there are things that can make their lives more fun and no longer have to worry about dying. Many are lucky to have technology that will allow them to have a long life. Organ transplants move or transfer (a part of the body) to another person, typically with some effort or upheaval. These surgeries are complicated and long. However, a doctor from Italy wants to be the first person to put a head on another body. To do this, he must have a volunteer. He got one. A man from Russia whose body is diseased, but his head and mind is fine. In fact, he is very smart. Will the first human head transplant happen soon? According to Sergio Canavero, it will – and he’ll be the man to do it.

In 2015, Canavero announced his intention to carry out the pioneering operation, with the head being that of a Russian man, Valery Spiridonov, who has a muscle degenerative disease. They are not sure who will be the donor body. More recently, Canavero has said that a Chinese patient will be the first to have their head transplanted. But he wants it to be the one who does the surgery.

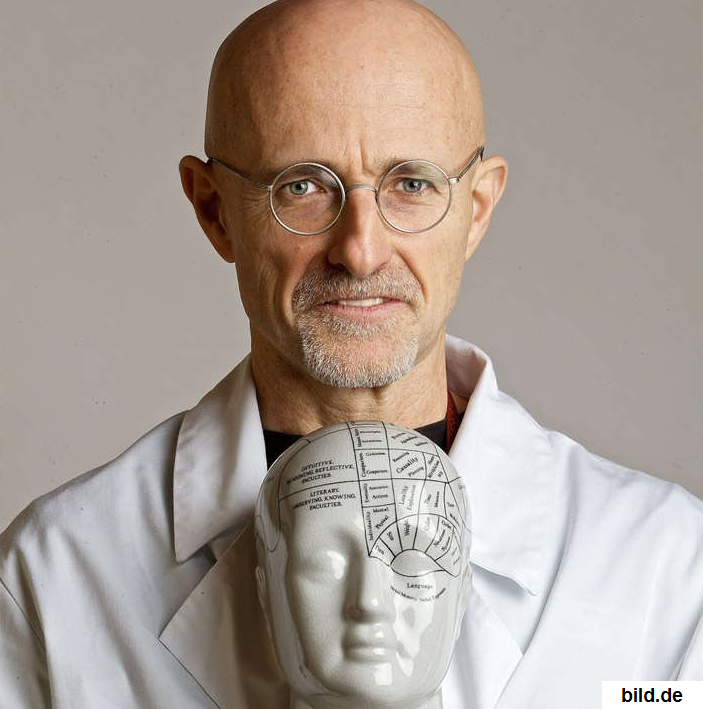

So who is Sergio Canavero, and what’s his background? The Turin-based Italian neurosurgeon has had a productive research career: his name appears on 112 papers on PubMed, dating back to 1990. His main interest is pain, specifically central pain syndromes, in which damage to the brain or spinal cord leads to chronic, often difficult-to-treat pain.

Canavero’s first paper on head transplantation was published in 2013 (in a journal that regular readers may be familiar with.) However, his interest in radical transplant surgery dates back 25 years: in 1992, Canavero published a speculative paper on “Total eye transplantation for the blind: a challenge for the future.” What if,” Canavero asked, “it were possible to implant a donor eye into a recipient’s socket, before connecting it up to the brain by encouraging the optic nerve to grow into place?” Although interested in this possiblity, he never revisited this idea.

The 2013 paper introduced two acronyms which Canavero has gone on to use regularly. HEAVEN, or “HEad Anastomosis VENture”, refers to the overall project to carry out the first human head transplant. GEMINI, the etymology of which is unclear, is the key procedure that will make the head transplant possible: the fusion, or connection, of two severed spinal cords into one. Spinal cord fusion or re-connection is, to put it mildly, a technical challenge. It’s the holy grail of spinal cord injury – the power to reconnect a severed spinal cord could allow countless people to move, and feel, again. But it isn’t easy.

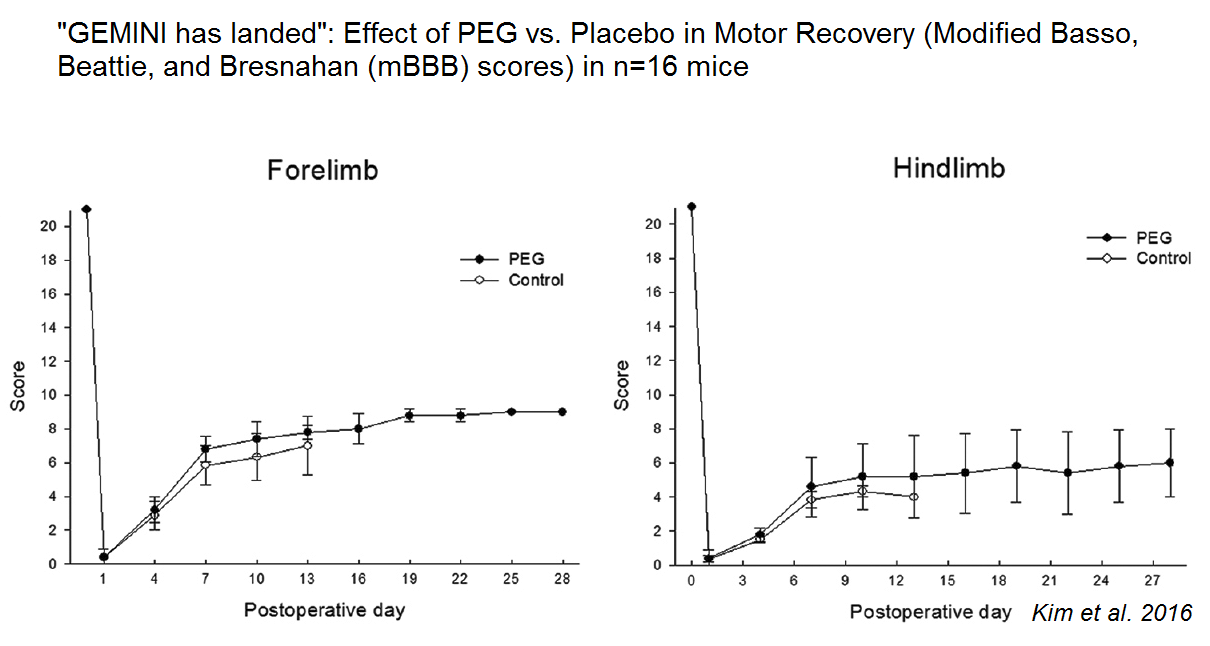

Canavero claims to have cracked the problem. In September 2016, Canavero announced that “GEMINI has landed – spinal cord fusion achieved.” The secret, he says, is a combination of a very sharp cut – to minimize damage to the nerve cells – and PEG, polyethylene glycol. PEG, Canavero says, has “the uncanny capacity to literally re-fuse neuronal cell membranes submitted to mechanical disruption.”

In the same issue of the journal, Canavero’s South Korean collaborator, C-Yoon Kim, reported that PEG produced “partial restoration of motor function” in mice whose spinal cords were severed. The Kim et al. paper is to date the only evidence that Canavero’s GEMINI works, and the results are not very impressive. Compared to a control group, the PEG-treated mice recovered slightly better from the lesion, but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. All of the control group and 3/8 of the PEG group died within 2 weeks

As well as mice, Kim et al. also studied the effects of PEG in re-fusing the spinal cords of rats, but the results of this experiment were inconclusive because most of the animals died due to “a storm that filled the underground lab.”

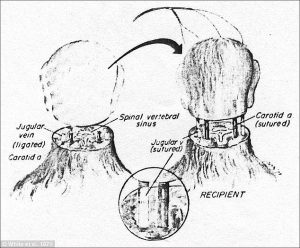

Beyond fusing the spinal cord, a head transplant would also require connecting up blood vessels, such that the head could receive blood from its new body. This is a technical challenge, although not perhaps as tricky as spinal cord fusion. As early as 1908, Charles Guthrie connected the head of a dog onto the body of another dog, and there have been several refinements of this eerie procedure since.

Canavero and a team of Chinese researchers recently reported the creation of a Cronenbergesque two-headed rat, although there was no attempt at spinal cord fusion here – just blood vessel redirection which allowed the second head to live attached to the other rat’s body (for 6 hours).

What about the ethics of all this? Are these animal experiments justified? And if Canavero ever gets his hands on a human patient, what then? Even on an optimistic view, someone undergoing this surgery runs a high risk of death, paralysis, or pain – the very central pain syndrome that Canavero spent his previous career studying and treating.

Even with the patient’s informed consent, it’s not clear that decapitation is compatible with the Hippocratic Oath. Perhaps Canavero will be able to find a hospital ethics committee somewhere willing to approve the study, but would that make it ethical? Here’s the words of a 2001 paper in the Lancet on the topic of ethics.