The Autobiography of Malcolm X part one: Nightmare

Consider the circumstances that birth revolutionary leaders. The personal experiences of Malcom X had a direct effect on the message that evolved from him over time. Leaders are not the ones who motivate or create the movement they are the manifestation of the collective circumstances that give life to the movement. They are not the fuel; they are the spark that is the fire of ignition. The feelings of resentment and rage are the fuel, the circumstances that cause these resentments are the oxygen that give life in the presence of the spark.

The will of the people is always a bottom up flow and its the will of the people that elevates the leader. Actual policy change comes only from the top down in a symbiotic relationship of democracy.

This chapter highlights not just Malcom X personally but the collective nightmare that was created for black individuals through systemic racism. There are two responses to this nightmare; 1) self destruction leading to a reactionary suicide through addiction, crime, self-loathing, etc. 2) the resilience of positive revolutionary action, to the extent of-if need be- a revolutionary suicide. Malcolm X almost went through the former but thank God he persevered in the latter.

-Reflections of young black man facing life in the 21st Century with gratitude for the legacy of El Hajj Malik El Shabazz/ Malcolm X

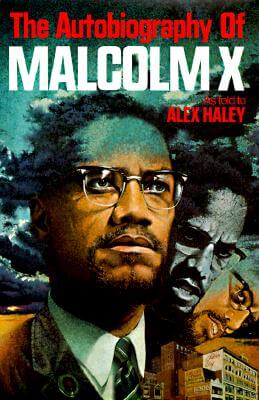

CHAPTER ONE

NIGHTMARE

When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders

galloped up to our home in Omaha, Nebraska, one night. Surrounding the house, brandishing

their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out. My mother went to the front

door and opened it. Standing where they could see her pregnant condition, she told them that she

was alone with her three small children, and that my father was away, preaching, in Milwaukee.

The Klansmen shouted threats and warnings at her that we had better get out of town because

“the good Christian white people” were not going to stand for my father’s “spreading trouble”

among the “good” Negroes of Omaha with the “back to Africa” preachings of Marcus Garvey[1].

My father, the Reverend Earl Little, was a Baptist minister, a dedicated organizer for Marcus

Aurelius Garvey’s U.N.I.A. (Universal Negro Improvement Association)[2]. With the help of such

disciples as my father, Garvey, from his headquarters in New York City’s Harlem, was raising the

banner of black-race purity and exhorting the Negro masses to return to their ancestral African

homeland-a cause which had made Garvey the most controversial black man on earth.

Still shouting threats, the Klansmen finally spurred their horses and galloped around the house,

shattering every window pane with their gun butts. Then they rode off into the night, their torches

flaring, as suddenly as they had come.

My father was enraged when he returned. He decided to wait until I was born-which would be

soon-and then the family would move. I am not sure why he made this decision, for he was not a

frightened Negro, as most then were, and many still are today. My father was a big, six-foot-four,

very black man. He had only one eye. How he had lost the other one I have never known. He was

from Reynolds, Georgia, where he had left school after the third or maybe fourth grade. He

believed, as did Marcus Garvey, that freedom, independence and self-respect could never be

achieved by the Negro in America, and that therefore the Negro should leave America to the

white man and return to his African land of origin. Among the reasons my father had decided to

risk and dedicate his life to help disseminate this philosophy among his people was that he had

seen four of his six brothers die by violence, three of them killed by white men, including one by

lynching. What my father could not know then was that of the remaining three, including himself,

only one, my Uncle Jim, would die in bed, of natural causes. Northern white police were later to

shoot my Uncle Oscar. And my father was finally himself to die by the white man’s hands.

It has always been my belief that I, too, will die by violence. I have done all that I can to be

prepared.

I was my father’s seventh child. He had three children by a previous marriage-Ella, Earl, and

Mary, who lived in Boston. He had met and married my mother in Philadelphia, where their first

child, my oldest full brother; Wilfred, was born. They moved from Philadelphia to Omaha, where

Hilda and then Philbert were born.

I was next in line. My mother was twenty-eight when I was born on May 19, 1925, in an Omaha

hospital. Then we moved to Milwaukee, where Reginald was born. From infancy, he had some

kind of hernia condition which was to handicap him physically for the rest of his life.

Louise Little, my mother, who was born in Grenada, in the British West Indies, looked like a white

woman. Her father was white. She had straight black hair, and her accent did not sound like a Negro’s. Of this white father of hers, I know nothing except her shame about it. I remember

hearing her say she was glad that she had never seen him. It was, of course, because of him that

I got my reddish-brown “mariny” color of skin, and my hair of the same color. I was the lightest

child in our family. (Out in the world later on, in Boston and New York, I was among the millions of

Negroes who were insane enough to feel that it was some kind of status symbol to be light

complexioned-that one was actually fortunate to be born thus. But, still later, I learned to hate

every drop of that white rapist’s[3] blood that is in me.)

Our family stayed only briefly in Milwaukee, for my father wanted to find a place where he could

raise our own food and perhaps build a business. The teaching of Marcus Garvey stressed

becoming independent of the white man. We went next, for some reason, to Lansing, Michigan.

My father bought a house and soon, as had been his pattern, he was doing free-lance Christian

preaching in local Negro Baptist churches, and during the week he was roaming about spreading

word of Marcus Garvey.

He had begun to lay away savings for the store he had always wanted to own when, as always,

some stupid local Uncle Tom Negroes began to funnel stories about his revolutionary beliefs to

the local white people. This time, the get-out-of-town threats came from a local hate society called

The Black Legion. They wore black robes instead of white. Soon, nearly everywhere my father

went, Black Legionnaires were reviling him as an “uppity nigger” for wanting to own a store, for

living outside the Lansing Negro district, for spreading unrest and dissention among “the good

niggers.”

As in Omaha, my mother was pregnant again, this time with my youngest sister. Shortly after

Yvonne was born came the nightmare night in 1929, my earliest vivid memory. I remember being

suddenly snatched awake into a frightening confusion of pistol shots and shouting and smoke

and flames. My father had shouted and shot at the two white men who had set the fire and were

running away. Our home was burning down around us. We were lunging and bumping and

tumbling all over each other trying to escape. My mother, with the baby in her arms, just made it

into the yard before the house crashed in, showering sparks. I remember we were outside in the

night in our underwear, crying and yelling our heads off. The white police and firemen came and

stood around watching as the house burned down to the ground.

My father prevailed on some friends to clothe and house us temporarily; then he moved us into

another house on the outskirts of East Lansing. In those days Negroes weren’t allowed after dark

in East Lansing proper. There’s where Michigan State University is located; I related all of this to

an audience of students when I spoke there in January, 1963 (and had the first reunion in a long

while with my younger brother, Robert, who was there doing postgraduate studies in psychology).

I told them how East Lansing harassed us so much that we had to move again, this time two

miles out of town, into the country. This was where my father built for us with his own hands a

four-room house. This is where I really begin to remember things-this home where I started to

grow up.

After the fire, I remember that my father was called in and questioned about a permit for the pistol

with which he had shot at the white men who set the fire. I remember that the police were always

dropping by our house, shoving things around, “just checking” or “looking for a gun.” The pistol

they were looking for-which they never found, and for which they wouldn’t issue a permit-was

sewed up inside a pillow. My father’s .22 rifle and his shotgun, though, were right out in the open;

everyone had them for hunting birds and rabbits and other game.

* * *

After that, my memories are of the friction between my father and mother. They seemed to be

nearly always at odds. Sometimes my father would beat her. It might have had something to do

with the fact that my mother had a pretty good education. Where she got it I don’t know. But an educated woman, I suppose, can’t resist the temptation to correct an uneducated man. Every now

and then, when she put those smooth words on him, he would grab her.

My father was also belligerent toward all of the children, except me. The older ones he would

beat almost savagely if they broke any of his rules-and he had so many rules it was hard to know

them all. Nearly all my whippings came from my mother. I’ve thought a lot about why. I actually

believe that as anti-white as my father was, he was subconsciously so afflicted with the white

man’s brainwashing of Negroes that he inclined to favor the light ones, and I was his lightest

child. Most Negro parents in those days would almost instinctively treat any lighter children better

than they did the darker ones. It came directly from the slavery tradition that the “mulatto,”

because he was visibly nearer to white, was therefore “better.”

My two other images of my father are both outside the home. One was his role as a Baptist

preacher. He never pastored in any regular church of his own; he was always a “visiting

preacher.” I remember especially his favorite sermon: “That little _black_ train is a-comin’ . . . an’

you better get all your business right!” I guess this also fit his association with the back-to-Africa

movement, with Marcus Garvey’s “Black Train Homeward.” My brother Philbert, the one just older

than me, loved church, but it confused and amazed me. I would sit goggle-eyed at my father

jumping and shouting as he preached, with the congregation jumping and shouting behind him,

their souls and bodies devoted to singing and praying. Even at that young age, I just couldn’t

believe in the Christian concept of Jesus as someone divine. And no religious person, until I was

a man in my twenties-and then in prison-could tell me anything. I had very little respect for most

people who represented religion.

It was in his role as a preacher that my father had most contact with the Negroes of Lansing.

Believe me when I tell you that those Negroes were in bad shape then. They are still in bad

shape-though in a different way. By that I mean that I don’t know a town with a higher percentage of complacent and misguided so-called “middle-class” Negroes-the typical status-symbol-oriented, integration-seeking type of Negroes. Just recently, I was standing in a lobby at the United Nations talking with an African ambassador and his wife, when a Negro came up to me and said, “You know me?” I was a little embarrassed because I thought he was someone I should remember. It turned out that he was one of those bragging, self-satisfied, “middle-class” Lansing

Negroes. I wasn’t ingratiated. He was the type who would never have been associated with

Africa, until the fad of having African friends became a status-symbol for “middle-class” Negroes.

Back when I was growing up, the “successful” Lansing Negroes were such as waiters and

bootblacks. To be a janitor at some downtown store was to be highly respected. The real “elite,”

the “big shots,” the “voices of the race,” were the waiters at the Lansing Country Club and the

shoeshine boys at the state capitol. The only Negroes who really had any money were the ones

in the numbers racket, or who ran the gambling houses, or who in some other way lived

parasitically off the poorest ones, who were the masses. No Negroes were hired then by

Lansing’s big Oldsmobile plant, or the Reo plant. (Do you remember the Reo? It was

manufactured in Lansing, and R. E. Olds, the man after whom it was named, also lived in

Lansing. When the war came along, they hired some Negro janitors.) The bulk of the Negroes

were either on Welfare, or W.P.A., or they starved.

The day was to come when our family was so poor that we would eat the hole out of a doughnut;

but at that time we were much better off than most town Negroes. The reason was that we raised

much of our own food out there in the country where we were. We were much better off than the

town Negroes who would shout, as my father preached, for the pie-in-the-sky and their heaven in

the hereafter while the white man had his here on earth.

I knew that the collections my father got for his preaching were mainly what fed and clothed us,

and he also did other odd jobs, but still the image of him that made me proudest was his

crusading and militant campaigning with the words of Marcus Garvey. As young as I was then, I

knew from what I overheard that my father was saying something that made him a “tough” man. I

remember an old lady, grinning and saying to my father, “You’re scaring these white folks to death!”

One of the reasons I’ve always felt that my father favored me was that to the best of my

remembrance, it was only me that he sometimes took with him to the Garvey U.N.I.A. meetings

which he held quietly in different people’s homes. There were never more than a few people at

any one time-twenty at most. But that was a lot, packed into someone’s living room. I noticed how

differently they all acted, although sometimes they were the same people who jumped and

shouted in church. But in these meetings both they and my father were more intense, more

intelligent and down to earth. It made me feel the same way.

I can remember hearing of “Adam driven out of the garden into the caves of Europe,” “Africa for

the Africans,” “Ethiopians, Awake!” And my father would talk about how it would not be much

longer before Africa would be completely run by Negroes-“by black men,” was the phrase he

always used.

“No one knows when the hour of Africa’s redemption cometh. It is in the wind. It is coming. One

day, like a storm, it will be here.”

I remember seeing the big, shiny photographs of Marcus Garvey that were passed from hand to

hand. My father had a big envelope of them that he always took to these meetings. The pictures

showed what seemed to me millions of Negroes thronged in parade behind Garvey riding in a fine

car, a big black man dressed in a dazzling uniform with gold braid on it, and he was wearing a

thrilling hat with tall plumes. I remember hearing that he had black followers not only in the United

States but all around the world, and I remember how the meetings always closed with my father

saying, several times, and the people chanting after him, “Up, you mighty race, you can

accomplish what you will!”

I have never understood why, after hearing as much as I did of these kinds of things, I somehow

never thought, then, of the black people in Africa. My image of Africa, at that time, was of naked

savages, cannibals, monkeys and tigers and steaming jungles.

My father would drive in his old black touring car, sometimes taking me, to meeting places all

around the Lansing area. I remember one daytime meeting (most were at night) in the town of

Owosso, forty miles from Lansing, which the Negroes called “White City.” (Owosso’s greatest

claim to fame is that it is the home town of Thomas E. Dewey.) As in East Lansing, no Negroes

were allowed on the streets there after dark-hence the daytime meeting. In point of fact, in those

days lots of Michigan towns were like that. Every town had a few “home” Negroes who lived

there. Sometimes it would be just one family, as in the nearby county seat, Mason, which had a

single Negro family named Lyons. Mr. Lyons had been a famous football star at Mason High

School, was highly thought of in Mason, and consequently he now worked around that town in

menial jobs.

My mother at this tune seemed to be always working-cooking, washing, ironing, cleaning, and

fussing over us eight children. And she was usually either arguing with or not speaking to my

father. One cause of friction was that she had strong ideas about what she wouldn’t eat-and didn’t

want _us_ to eat-including pork and rabbit, both of which my father loved dearly.

He was a real Georgia Negro, and he believed in eating plenty of what we in Harlem today call

“soul food.”

I’ve said that my mother was the one who whipped me-at least she did whenever she wasn’t

ashamed to let the neighbors think she was killing me. For if she even acted as though she was

about to raise her hand to me, I would open my mouth and let the world know about it. If anybody

was passing by out on the road, she would either change her mind or just give me a few licks.

Thinking about it now, I feel definitely that just as my father favored me for being lighter than the

other children, my mother gave me more hell for the same reason. She was very light herself but she favored the ones who were darker. Wilfred, I know, was particularly her angel. I remember

that she would tell me to get out of the house and “Let the sun shine on you so you can get some

color.” She went out of her way never to let me become afflicted with a sense of color-superiority.

I am sure that she treated me this way partly because of how she came to be light herself.

I learned early that crying out in protest could accomplish things. My older brothers and sister had

started to school when, sometimes, they would come in and ask for a buttered biscuit or

something and my mother, impatiently, would tell them no. But I would cry out and make a fuss

until I got what I wanted. I remember well how my mother asked me why I couldn’t be a nice boy

like Wilfred; but I would think to myself that Wilfred, for being so nice and quiet, often stayed

hungry. So early in life, I had learned that if you want something, you had better make some

noise.

Not only did we have our big garden, but we raised chickens. My father would buy some baby

chicks and my mother would raise them. We all loved chicken. That was one dish there was no

argument with my father about. One thing in particular that I remember made me feel grateful

toward my mother was that one day I went and asked her for my own garden, and she did let me

have my own little plot. I loved it and took care of it well. I loved especially to grow peas. I was

proud when we had them on our table. I would pull out the grass in my garden by hand when the

first little blades came up. I would patrol the rows on my hands and knees for any worms and

bugs, and I would kill and bury them. And sometimes when I had everything straight and clean for

my things to grow, I would lie down on my back between two rows, and I would gaze up in the

blue sky at the clouds moving and think all kinds of things.

At five, I, too, began to go to school, leaving home in the morning along with Wilfred, Hilda, and

Philbert. It was the Pleasant Grove School that went from kindergarten through the eighth grade.

It was two miles outside the city limits, and I guess there was no problem about our attending

because we were the only Negroes in the area. In those days white people in the North usually

would “adopt” just a few Negroes; they didn’t see them as any threat. The white kids didn’t make

any great thing about us, either. They called us “nigger” and “darkie” and “Rastus” so much that

we thought those were our natural names. But they didn’t think of it as an insult; it was just the

way they thought about us.

* * *

One afternoon in 1931 when Wilfred, Hilda, Philbert, and I came home, my mother and father

were having one of their arguments. There had lately been a lot of tension around the house

because of Black Legion threats. Anyway, my father had taken one of the rabbits which we were

raising, and ordered my mother to cook it. We raised rabbits, but sold them to whites. My father

had taken a rabbit from the rabbit pen. He had pulled off the rabbit’s head. He was so strong, he

needed no knife to behead chickens or rabbits. With one twist of his big black hands he simply

twisted off the head and threw the bleeding-necked thing back at my mother’s feet.

My mother was crying. She started to skin the rabbit, preparatory to cooking it. But my father was

so angry he slammed on out of the front door and started walking up the road toward town.

It was then that my mother had this vision. She had always been a strange woman in this sense,

and had always had a strong intuition of things about to happen. And most of her children are the

same way, I think. When something is about to happen, I can feel something, sense something. I

never have known something to happen that has caught me completely off guard-except once.

And that was when, years later, I discovered facts I couldn’t believe about a man who, up until

that discovery, I would gladly have given my life for.

My father was well up the road when my mother ran screaming out onto the porch. _”Early!

Early!”_ She screamed his name. She clutched up her apron in one hand, and ran down across

the yard and into the road. My father turned around. He saw her.

For some reason, considering how angry he had been when he left, he waved at her. But he kept on going.

She told me later, my mother did, that she had a vision of my father’s end. All the rest of the

afternoon, she was not herself, crying and nervous and upset. She finished cooking the rabbit

and put the whole thing in the warmer part of the black stove. When my father was not back

home by our bedtime, my mother hugged and clutched us, and we felt strange, not knowing what

to do, because she had never acted like that.

I remember waking up to the sound of my mother’s screaming again. When I scrambled out, I

saw the police in the Irving room; they were trying to calm her down. She had snatched on her

clothes to go with them. And all of us children who were staring knew without anyone having to

say it that something terrible had happened to our father.

My mother was taken by the police to the hospital, and to a room where a sheet was over my

father in a bed, and she wouldn’t look, she was afraid to look. Probably it was wise that she didn’t.

My father’s skull, on one side, was crushed in, I was told later. Negroes in Lansing have always

whispered that he was attacked, and then laid across some tracks for a streetcar to run over him.

His body was cut almost in half.

He lived two and a half hours in that condition. Negroes then were stronger than they are now,

especially Georgia Negroes. Negroes born in Georgia had to be strong simply to survive.

It was morning when we children at home got the word that he was dead. I was six. I can

remember a vague commotion, the house filled up with people crying, saying bitterly that the

white Black Legion had finally gotten him. My mother was hysterical. In the bedroom, women

were holding smelling salts under her nose. She was still hysterical at the funeral.

I don’t have a very clear memory of the funeral, either. Oddly, the main thing I remember is that it

wasn’t in a church, and that surprised me, since my father was a preacher, and I had been where

he preached people’s funerals in churches. But his was in a funeral home.

And I remember that during the service a big black fly came down and landed on my father’s face,

and Wilfred sprang up from his chair and he shooed the fly away, and he came groping back to

his chair-there were folding chairs for us to sit on-and the tears were streaming down his face.

When we went by the casket, I remember that I thought that it looked as if my father’s strong

black face had been dusted with flour, and I wished they hadn’t put on such a lot of it.

Back in the big four-room house, there were many visitors for another week or so. They were

good friends of the family, such as the Lyons from Mason, twelve miles away, and the Walkers,

McGuires, Liscoes, the Greens, Randolphs, and the Turners, and others from Lansing, and a lot

of people from other towns, whom I had seen at the Garvey meetings.

We children adjusted more easily than our mother did. We couldn’t see, as clearly as she did, the

trials that lay ahead. As the visitors tapered off, she became very concerned about collecting the

two insurance policies that my father had always been proud he carried.

He had always said that families should be protected in case of death. One policy apparently paid off without any problem- the smaller one. I don’t know the amount of it. I would imagine it was not more than a thousand dollars, and maybe half of that.

But after that money came, and my mother had paid out a lot of it for the funeral and expenses,

she began going into town and returning very upset. The company that had issued the bigger

policy was balking at paying off. They were claiming that my father had committed suicide.

Visitors came again, and there was bitter talk about white people: how could my father bash

himself in the head, then get down across the streetcar tracks to be run over?

So there we were. My mother was thirty-four years old now, with no husband, no provider or

protector to take care of her eight children. But some kind of a family routine got going again. And for as long as the first insurance money lasted, we did all right.

Wilfred, who was a pretty stable fellow, began to act older than his age. I think he had the sense

to see, when the rest of us didn’t, what was in the wind for us. He quietly quit school and went to

town in search of work. He took any kind of job he could find and he would come home, dog-tired,

in the evenings, and give whatever he had made to my mother.

Hilda, who always had been quiet, too, attended to the babies. Philbert and I didn’t contribute

anything. We just fought all the time-each other at home, and then at school we would team up

and fight white kids. Sometimes the fights would be racial in nature, but they might be about

anything.

Reginald came under my wing. Since he had grown out of the toddling stage, he and I had

become very close. I suppose I enjoyed the fact that he was the little one, under me, who looked

up to me.

My mother began to buy on credit. My father had always been very strongly against credit. “Credit

is the first step into debt and back into slavery,” he had always said. And then she went to work

herself. She would go into Lansing and find different jobs-in housework, or sewing-for white

people. They didn’t realize, usually, that she was a Negro. A lot of white people around there

didn’t want Negroes in their houses.

She would do fine until in some way or other it got to people who she was, whose widow she

was. And then she would be let go. I remember how she used to come home crying, but trying to

hide it, because she had lost a job that she needed so much.

Once when one of us-I cannot remember which-had to go for something to where she was

working, and the people saw us, and realized she was actually a Negro, she was fired on the

spot, and she came home crying, this time not hiding it.

When the state Welfare people began coming to our house, we would come from school

sometimes and find them talking with our mother, asking a thousand questions. They acted and

looked at her, and at us, and around in our house, in a way that had about it the feeling-at least

for me-that we were not people. In their eyesight we were just _things_, that was all.

My mother began to receive two checks-a Welfare check and, I believe, widow’s pension. The

checks helped. But they weren’t enough, as many of us as there were. When they came, about

the first of the month, one always was already owed in full, if not more, to the man at the grocery

store. And, after that, the other one didn’t last long.

We began to go swiftly downhill. The physical downhill wasn’t as quick as the psychological. My

mother was, above everything else, a proud woman, and it took its toll on her that she was

accepting charity. And her feelings were communicated to us.

She would speak sharply to the man at the grocery store for padding the bill, telling him that she

wasn’t ignorant, and he didn’t like that. She would talk back sharply to the state Welfare people,

telling them that she was a grown woman, able to raise her children, that it wasn’t necessary for

them to keep coming around so much, meddling in our lives. And they didn’t like that.

But the monthly Welfare check was their pass. They acted as if they owned us, as if we were their

private property. As much as my mother would have liked to, she couldn’t keep them out. She

would get particularly incensed when they began insisting upon drawing us older children aside, one at a time, out on the porch or somewhere, and asking us questions, or telling us things-

against our mother and against each other.{}

We couldn’t understand why, if the state was willing to give us packages of meat, sacks of potatoes and fruit, and cans of all kinds of things, our mother obviously hated to accept. We really

couldn’t understand. What I later understood was that my mother was making a desperate effort

to preserve her pride-and ours.{}

Pride was just about all we had to preserve, for by 1934, we really began to suffer. This was

about the worst depression year, and no one we knew had enough to eat or live on. Some old

family friends visited us now and then. At first they brought food. Though it was charity, my mother

took it.

Wilfred was working to help. My mother was working, when she could find any kind of job. In

Lansing, there was a bakery where, for a nickel, a couple of us children would buy a tall flour sack

of day-old bread and cookies, and then walk the two miles back out into the country to our house.

Our mother knew, I guess, dozens of ways to cook things with bread and out of bread. Stewed

tomatoes with bread, maybe that would be a meal. Something like French toast, if we had any

eggs. Bread pudding, sometimes with raisins in it. If we got hold of some hamburger, it came to

the table more bread than meat. The cookies that were always in the sack with the bread, we just

gobbled down straight.

But there were times when there wasn’t even a nickel and we would be so hungry we were dizzy.

My mother would boil a big pot of dandelion greens, and we would eat that. I remember that

some small-minded neighbor put it out, and children would tease us, that we ate “fried grass.”

Sometimes, if we were lucky, we would have oatmeal or cornmeal mush three times a day. Or

mush in the morning and cornbread at night.

Philbert and I were grown up enough to quit fighting long enough to take the .22 caliber rifle that

had been our father’s, and shoot rabbits that some white neighbors up or down the road would

buy. I know now that they just did it to help us, because they, like everyone, shot their own

rabbits. Sometimes, I remember, Philbert and I would take little Reginald along with us. He wasn’t

very strong, but he was always so proud to be along. We would trap muskrats out in the little

creek in back of our house. And we would lie quiet until unsuspecting bullfrogs appeared, and we

would spear them, cut off their legs, and sell them for a nickel a pair to people who lived up and

down the road. The whites seemed less restricted in their dietary tastes.

Then, about in late 1934, I would guess, something began to happen. Some kind of psychological

deterioration hit our family circle and began to eat away our pride. Perhaps it was the constant

tangible evidence that we were destitute.{} We had known other families who had gone on relief.

We had known without anyone in our home ever expressing it that we had felt prouder not to be

at the depot where the free food was passed out. And, now, we were among them. At school, the

“on relief” finger suddenly was pointed at us, too, and sometimes it was said aloud.

It seemed that everything to eat in our house was stamped Not To Be Sold. All Welfare food bore

this stamp to keep the recipients from selling it. It’s a wonder we didn’t come to think of Not To Be

Sold as a brand name.

Sometimes, instead of going home from school, I walked the two miles up the road into Lansing. I

began drifting from store to store, hanging around outside where things like apples were

displayed in boxes and barrels and baskets, and I would watch my chance and steal me a treat.

You know what a treat was to me? Anything!

Or I began to drop in about dinnertime at the home of some family that we knew. I knew that they

knew exactly why I was there, but they never embarrassed me by letting on. They would invite

me to stay for supper, and I would stuff myself.

Especially, I liked to drop in and visit at the Gohannases’ home. They were nice, older people,

and great churchgoers. I had watched them lead the jumping and shouting when my father

preached. They had, living with them-they were raising him-a nephew whom everyone called “Big

Boy,” and he and I got along fine. Also living with the Gohannases was old Mrs. Adcock, who went with them to church. She was always trying to help anybody she could, visiting anyone she

heard was sick, carrying them something. She was the one who, years later, would tell me

something that I remembered a long time: “Malcolm,there’s one thing I like about you. You’re no

good, but you don’t try to hide it. You are not a hypocrite.”

The more I began to stay away from home and visit people and steal from the stores, the more

aggressive I became in my inclinations. I never wanted to wait for anything.

I was growing up fast, physically more so than mentally. As I began to be recognized more

around the town, I started to become aware of the peculiar attitude of white people toward me. I

sensed that it had to do with my father. It was an adult version of what several white children had

said at school, in hints, or sometimes in the open, which really expressed what their parents had

said-that the Black Legion or the Klan had killed my father, and the insurance company had

pulled a fast one in refusing to pay my mother the policy money.

When I began to get caught stealing now and then, the state Welfare people began to focus on

me when they came to our house. I can’t remember how I first became aware that they were

talking of taking me away. What I first remember along that line was my mother raising a storm

about being able to bring up her own children. She would whip me for stealing, and I would try to

alarm the neighborhood with my yelling. One thing I have always been proud of is that I never

raised my hand against my mother.

In the summertime, at night, in addition to all the other things we did, some of us boys would slip

out down the road, or across the pastures, and go “cooning” watermelons. White people always

associated watermelons with Negroes, and they sometimes called Negroes “coons” among all

the other names, and so stealing watermelons became “cooning” them. If white boys were doing

it, it implied that they were only acting like Negroes. Whites have always hidden or justified all of

the guilts they could by ridiculing or blaming Negroes.

One Halloween night, I remember that a bunch of us were out tipping over those old country

outhouses, and one old farmer-I guess he had tipped over enough in his day-had set a trap for

us. Always, you sneak up from behind the outhouse, then you gang together and push it, to tip it

over. This farmer had taken his outhouse off the hole, and set it just in _front_ of the hole. Well,

we came sneaking up in single file, in the darkness, and the two white boys in the lead fell down

into the outhouse hole neck deep. They smelled so bad it was all we could stand to get them out,

and that finished us all for that Halloween. I had just missed falling in myself. The whites were so

used to taking the lead, this time it had really gotten them in the hole.

Thus, in various ways, I learned various things. I picked strawberries, and though I can’t recall

what I got per crate for picking, I remember that after working hard all one day, I wound up with

about a dollar, which was a whole lot of money in those times. I was so hungry, I didn’t know what

to do. I was walking away toward town with visions of buying something good to eat, and this

older white boy I knew, Richard Dixon, came up and asked me if I wanted to match nickels. He

had plenty of change for my dollar. In about a half hour, he had all the change back, including my

dollar, and instead of going to town to buy something, I went home with nothing, and I was bitter.

But that was nothing compared to what I felt when I found out later that he had cheated. There is

a way that you can catch and hold the nickel and make it come up the way you want. This was

my first lesson about gambling: if you see somebody winning all the time, he isn’t gambling, he’s

cheating. Later on in life, if I were continuously losing in any gambling situation, I would watch

very closely. It’s like the Negro in America seeing the white man win all the time. He’s a

professional gambler; he has all the cards and the odds stacked on his side, and he has always

dealt to our people from the bottom of the deck.

About this time, my mother began to be visited by some Seventh Day Adventists who had moved

into a house not too far down the road from us. Theywould talk to her for hours at a time, and

leave booklets and leaflets and magazines for her to read. She read them, and Wilfred, who had

started back to school after we had begun to get the relief food supplies, also read a lot. His head was forever in some book.

Before long, my mother spent much time with the Adventists. It’s my belief that what mostly

influenced her was that they had even more diet restrictions than she always had taught and

practiced with us. Like us, they were against eating rabbit and pork; they followed the Mosaic

dietary laws. They ate nothing of the flesh without a split hoof, or that didn’t chew a cud. We

began to go with my mother to the Adventist meetings that were held further out in the country.

For us children, I know that the major attraction was the good food they served. But we listened,

too. There were a handful of Negroes, from small towns in the area, but I would say that it was

ninety-nine percent white people. The Adventists felt that we were living at the end of time, that

the world soon was coming to an end. But they were the friendliest white people I had ever seen.

In some ways, though, we children noticed, and, when we were back at home, discussed, that

they were different from us-such as the lack of enough seasoning in their food, and the different

way that white people smelled.

* * *

Meanwhile, the state Welfare people kept after my mother. By now, she didn’t make it any secret

that she hated them, and didn’t want them in her house. But they exerted their right to come, and

I have many, many times reflected upon how, talking to us children, they began to plant the seeds

of division in our minds. They would ask such things as who was smarter than the other. And they

would ask me why I was “so different.”

I think they felt that getting children into foster homes was a legitimate pan of their function, and

the result would be less troublesome, however they went about it.

And when my mother fought them, they went after her-first, through me. I was the first target. I

stole; that implied that I wasn’t being taken care of by my mother.

All of us were mischievous at some time or another, I more so than any of the rest. Philbert and I

kept a battle going. And this was just one of a dozen things that kept building up the pressure on

my mother.

I’m not sure just how or when the idea was first dropped by the Welfare workers that our mother

was losing her mind.

But I can distinctly remember hearing “crazy” applied to her by them when they learned that the

Negro fanner who was in the next house down the road from us had offered to give us some

butchered pork-a whole pig, maybe even two of them-and she had refused. We all heard them

call my mother “crazy” to her face for refusing good meat. It meant nothing to them even when

she explained that we had never eaten pork, that it was against her religion as a Seventh Day

Adventist.

They were as vicious as vultures. They had no feelings, understanding, compassion, or respect

for my mother. They told us, “She’s crazy for refusing food.” Right then was when our home, our

unity, began to disintegrate. We were having a hard time, and I wasn’t helping. But we could have

made it, we could have stayed together. As bad as I was, as much trouble and worry as I caused

my mother, I loved her.

The state people, we found out, had interviewed the Gohannas family, and the Gohannases had said that they would take me into their home. My mother threw a fit, though, when she heard that-

and the home wreckers took cover for a while.

It was about this time that the large, dark man from Lansing began visiting. I don’t remember how

or where he and my mother met. It may have been through some mutual friends. I don’t

remember what the man’s profession was. In 1935, in Lansing, Negroes didn’t have anything you could call a profession. But the man, big and black, looked something like my father. I can

remember his name, but there’s no need to mention it. He was a single man, and my mother was

a widow only thirty-six years old. The man was independent; naturally she admired that. She was

having a hard time disciplining us, and a big man’s presence alone would help. And if she had a

man to provide, it would send the state people away forever.

We all understood without ever saying much about it. Or at least we had no objection. We took it

in stride, even with some amusement among us, that when the man came, our mother would be

all dressed up in the best that she had-she still was a good-looking woman-and she would act

differently, light-hearted and laughing, as we hadn’t seen her act in years.

It went on for about a year, I guess. And then, about 1936, or 1937, the man from Lansing jilted

my mother suddenly. He just stopped coming to see her. From what I later understood, he finally

backed away from taking on the responsibility of those eight mouths to feed. He was afraid of so

many of us. To this day, I can see the trap that Mother was in, saddled with all of us. And I can

also understand why he would shun taking on such a tremendous responsibility.

But it was a terrible shock to her.

It was the beginning of the end of reality for my mother. When she began to sit around and walk around talking to herself-almost as though she was unaware that we were there-it became increasingly terrifying.

The state people saw her weakening. That was when they began the definite steps to take me

away from home. They began to tell me how nice it was going to be at the Gohannases’ home,

where the Gohannases and Big Boy and Mrs. Adcock had all said how much they liked me, and

would like to have me live with them.

I liked all of them, too. But I didn’t want to leave Wilfred. I looked up to and admired my big

brother. I didn’t want to leave Hilda, who was like my second mother. Or Philbert; even in our

fighting, there was a feeling of brotherly union. Or Reginald, especially, who was weak with his

hernia condition, and who looked up to me as his big brother who looked out for him, as I looked

up to Wilfred. And I had nothing, either, against the babies, Yvonne, Wesley, and Robert.

As my mother talked to herself more and more, she gradually became less responsive to us. And

less responsible. The house became less tidy. We began to be more unkempt. And usually, now,

Hilda cooked.

We children watched our anchor giving way. It was something terrible that you couldn’t get your

hands on, yet you couldn’t get away from. It was a sensing that something bad was going to

happen. We younger ones leaned more and more heavily on the relative strength of Wilfred and

Hilda, who were the oldest.

When finally I was sent to the Gohannases’ home, at least in a surface way I was glad. I

remember that when I left home with the state man, my mother said one thing: “Don’t let them

feed him any pig.”

It was better, in a lot of ways, at the Gohannases’. Big Boy and I shared his room together, and we

hit it off nicely. He just wasn’t the same as my blood brothers. The Gohannases were very

religious people. Big Boy and I attended church with them. They were sanctified Holy Rollers

now. The preachers and congregations jumped even higher and shouted even louder than the

Baptists I had known. They sang at the top of their lungs, and swayed back and forth and cried

and moaned and beat on tambourines and chanted. It was spooky, with ghosts and spirituals and

“ha’nts” seeming to be in the very atmosphere when finally we all came out of the church, going

back home.

The Gohannases and Mrs. Adcock loved to go fishing, and some Saturdays Big Boy and I would

go along. I had changed schools now, to Lansing’s West Junior High School. It was right in the heart of the Negro community, and a few white kids were there, but Big Boy didn’t mix much with

any of our schoolmates, and I didn’t either. And when we went fishing, neither he nor I liked the

idea of just sitting and waiting for the fish to jerk the cork under the water-or make the tight line quiver, when we fished that way. I figured there should be some smarter way to get the fish-

though we never discovered what it might be.{foregrounding future tenet}

Mr. Gohannas was close cronies with some other men who, some Saturdays, would take me and

Big Boy with them hunting rabbits. I had my father’s .22 caliber rifle; my mother had said it was all

right for me to take it with me. The old men had a set rabbit-hunting strategy that they had always

used. Usually when a dog jumps a rabbit, and the rabbit gets away, that rabbit will always

somehow instinctively run in a circle and return sooner or later past the very spot where he

originally was jumped. Well, the old men would just sit and wait in hiding somewhere for the rabbit

to come back, then get their shots at him. I got to thinking about it, and finally I thought of a plan. I

would separate from them and Big Boy and I would go to a point where I figured that the rabbit,

returning, would have to pass me first.

It worked like magic. I began to get three and four rabbits before they got one. The astonishing

thing was that none of the old men ever figured out why. They outdid themselves exclaiming what

a sure shot I was. I was about twelve, then. All I had done was to improve on their strategy, and it

was the beginning of a very important lesson in life-that anytime you find someone more

successful than you are, especially when you’re both engaged in the same business-you know

they’re doing something that you aren’t.{future tenet}

I would return home to visit fairly often. Sometimes Big Boy and one or another, or both, of the

Gohannases would go with me-sometimes not. I would be glad when some of them did go,

because it made the ordeal easier.

Soon the state people were making plans to take over all of my mother’s children. She talked to

herself nearly all of the time now, and there was a crowd of new white people entering the picture-

always asking questions. They would even visit me at the Gohannases’. They would ask me questions out on the porch, or sitting out in their cars.

Eventually my mother suffered a complete breakdown, and the court orders were finally signed.

They took her to the State Mental Hospital at Kalamazoo.

It was seventy-some miles from Lansing, about an hour and a half on the bus. A Judge McClellan

in Lansing had authority over me and all of my brothers and sisters. We were “state children,”

court wards; he had the full say-so over us. A white man in charge of a black man’s children!

Nothing but legal, modern slavery-however kindly intentioned.{}

* * *

My mother remained in the same hospital at Kalamazoo for about twenty-six years. Later, when I

was still growing up in Michigan, I would go to visit her every so often. Nothing that I can imagine

could have moved me as deeply as seeing her pitiful state. In 1963, we got my mother out of the

hospital, and she now lives there in Lansing with Philbert and his family.

It was so much worse than if it had been a physical sickness, for which a cause might be known,

medicine given, a cure effected. Every time I visited her, when finally they led her-a case, a

number-back inside from where we had been sitting together, I felt worse.

My last visit, when I knew I would never come to see her again-there-was in 1952. I was twenty-

seven. My brother Philbert had told me that on his last visit, she had recognized him somewhat.

“In spots,” he said.

But she didn’t recognize me at all.

She stared at me. She didn’t know who I was.

Her mind, when I tried to talk, to reach her, was somewhere else. I asked, “Mama, do you know

what day it is?”

She said, staring, “All the people have gone.”

I can’t describe how I felt. The woman who had brought me into the world, and nursed me, and

advised me, and chastised me, and loved me, didn’t know me. It was as if I was trying to walk up

the side of a hill of feathers. I looked at her. I listened to her “talk.” But there was nothing I could

do.

I truly believe that if ever a state social agency destroyed a family, it destroyed ours. We wanted

and tried to stay together. Our home didn’t have to be destroyed. But the Welfare, the courts, and

their doctor, gave us the one-two-three punch. And ours was not the only case of this kind.{}

I knew I wouldn’t be back to see my mother again because it could make me a very vicious and

dangerous person-knowing how they had looked at us as numbers and as a case in their book,

not as human beings. And knowing that my mother in there was a statistic that didn’t have to be,

that existed because of a society’s failure, hypocrisy, greed, and lack of mercy and compassion.

Hence I have no mercy or compassion in me for a society that will crush people, and then

penalize them for not being able to stand up under the weight.{}

I have rarely talked to anyone about my mother, for I believe that I am capable of killing a person,

without hesitation, who happened to make the wrong kind of remark about my mother. So I

purposely don’t make any opening for some fool to step into.

Back then when our family was destroyed, in 1937, Wilfred and Hilda were old enough so that the

state let them stay on their own in the big four-room house that my father had built. Philbert was

placed with another family in Lansing, a Mrs. Hackett, while Reginald and Wesley went to live

with a family called Williams, who were friends of my mother’s. And Yvonne and Robert went to

live with a West Indian family named McGuire.

Separated though we were, all of us maintained fairly close touch around Lansing-in school and

out-whenever we could get together. Despite the artificially created separation and distance

between us, we still remained very close in our feelings toward each other.